Vadi or sun-dried lentil dumplings are traditional foods made to enrich the meals with proteins or substitute green vegetables when they are in scarcity or not permitted (in Jainism). The hand-dropped Gujarati Vadi are made using a variety of lentils, green moong dal, yellow moong dal or chora dal (black-eyed beans lentils), the last being the most preferred for its easy digestibility. Vadi has culinary as well as cultural significance and Vadi are part of a bride’s trousseau. The wedding festivities are kicked off with a Vadi and Papad making ceremony where the women in the family come together to make the Vadis and papad the bride eventually will take along. Like rolling Rotis and papad, Vadi making is a skill the girls were taught before they were married. Since everyone knew how to make Vadi it remained rather under-appreciated and undervalued skill. However, like numerous other traditional culinary skills, Vadi making is a fading skill and one understands and appreciates a good Vadi only after one has tasted both. It was Avani, who during the making of Kakdi+Vadi subzi enlightened me about the nuances of a good Vadi! Yes, you read it right. The petit, marble-sized dumpling has to be made right to taste right. And it has nuances to it. Trust me, there are art, craft and heart involved in making a good Vadi.

So what is a good Vadi:

A good Vadi is both delicate and strong at the same time. It is light to hold, is crisp outside and airy inside. It is so tender that one can steam cook it in 2-3 minutes. The key is to use Chora Dal Vadi, the moong dal vadi become tough after drying. The colour has to be light and creamy even after they have sunbathed for a couple of days. The Vadi has to cook and hold its shape once cooked. Oh yes, it’s an exhaustive list…

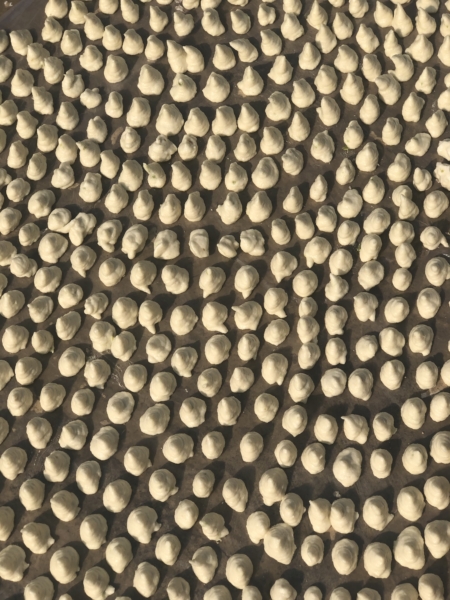

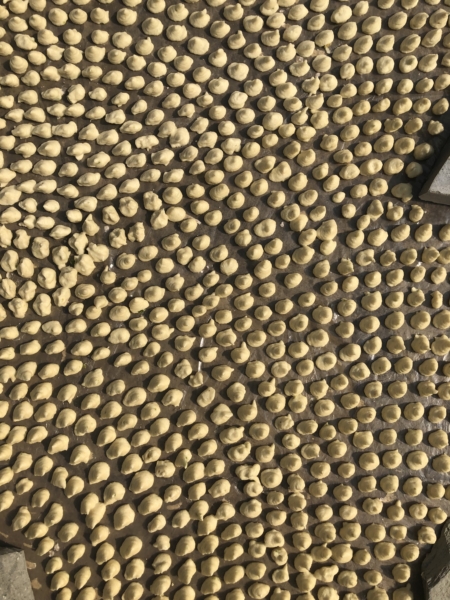

I decided to document the Vadi making with Jigishaben, the person Avani buys her Vad from. It took me 6 months to meet Jigishaben and do this story. Jigishaben along with her husband Ketanbhai, runs a home business and insists on quality over shortcuts. Ahmedabad is notorious for its heat. To beat the scorching heat, the couple is required to begin their preparations very early in the morning. The Dal is soaked at 3 a.m. as Jainism prohibits overnight soaking of pulses, lentils or batters. After 3-4 hours of soaking the dal is ready to be ground. Traditionally, the dal for Vadi is always ground in the Kundi-Dhoko. Since the contraption is difficult to source these days, Jigishaben grinds the dal in the mixer grinder and aerates it with an electric beater. The aeration is key to the delicate and soft interior. Once the dal is crushed the couple move to the terrace to proceed with the next stage of Vadi making. The batter is seasoned with salt, minimally spiced with crushed green chillies and aerated before hand-dropped on clean plastic sheets. Jigishaben is a one women show, functioning mostly without any help as she has little trust in others when it comes to adhering with quality and hygiene standards that she maintains. Ketanbhai is the only assistance she has. In the Ahmedabadi heat, Vadi making is a back burning task. The total output remains low if she drops them by hand hence, she pipes them by repurposing the milk bags as piping bags. That way her husband can pitch in too.

It indeed is back burning work but, Jigishaben sticks to her rules. ” I am what I am just because I am true to my values. God has been kind and has granted my wishes. My daughters studied well, are settled in life, we have good health what more can I ask for?? I never compromise on my work ethics, nor do I compromise on the price. Yes, some customers argue I charge more but they do not see the work involved in giving them the product they love. These Vadi, they would offer to the visiting saints or eat during fasting. It is true everyone knew how to make Vadi, but my daughters never learnt the skill from me. They do not want to as they feel I would seek their assistance while they are happy doing their desk jobs. This is too much work for them, work that does not bring money. I do it because I love this craft. It brings me deep satisfaction. It makes me happy!! ”

I stood on the terrace interacting on the nuances of making Vadi, deeply admiring the patterns she created while dropping the vadis and other sun-dried foods she makes between our discussions on life in general. It took the couple two hours to finish 2 kilos of batter. Waking up at wee hours to soak the dal so that the Vadi remain kosher for Jains, an hour of grinding and beating and 30-40 minutes to drop the wadis that are sold at Rs. 230 / $ 3.22 per kilogram. “It takes us 1.25 kilo gram of dal to make a kilo vadi, the ingredient cost would be around Rs. 150. No one takes into consideration the labour that goes into making it,” Jigishaben explains with utmost honesty. Imagine how we never miss a chance to haggle for a mere 10-20 rupees for foods made with so much care, love and integrity.

I am sure these pictures will live you spellbound as much as they did to me…❤️

No Comments